Roland Garros: When It Rains, It Pours

On tennis, climate change, and adaptation

One unwelcome guest at this year’s Roland Garros is a spector that more typically haunts Wimbledon: the rain. With the rain wiping out much of the outer court play on Wednesday and Thursday (and potentially more), tournament scheduling has become increasingly messy as there simply aren’t enough courts or dry hours of the day to get through the early rounds of the tournament. The rain not only poses a challenge to the administration of the tournament (especially with disappointed spectators claiming refunds on grounds passes), but also exacerbates pre-existing tensions regarding court scheduling.

In particular, debates about who is scheduled on the main court and who is placed on a “parking lot” have been reignited, not to mention continued discourse about the “match of the day” night session. Both cases illustrate how delicate tournament scheduling can be in the best of times, let alone when the weather refuses to cooperate. Additionally, the scheduling of previously postponed matches after new matches has further exacerbated the backlog that the tournament already has to get through.

Then, there’s the question of an empty Phillipe Chatrier when thousands of tennis fans keep getting sent home due to the weather. While Osaka and Swiatek played what will potentially be the match of the tournament, much of the stadium appeared to be empty, especially the best seats. The contrast between the business-funded prime seats and die hard fans with ground passes missing out on a day of tennis could not have been more stark.

These issues haven’t been as prevalent in past years, as this is one of the wettest Roland Garros’s on record. The question is therefore probably better posed as a meteorological rather than an administrative one: where is all this rain coming from, and how can the tournament adapt to deal with it?

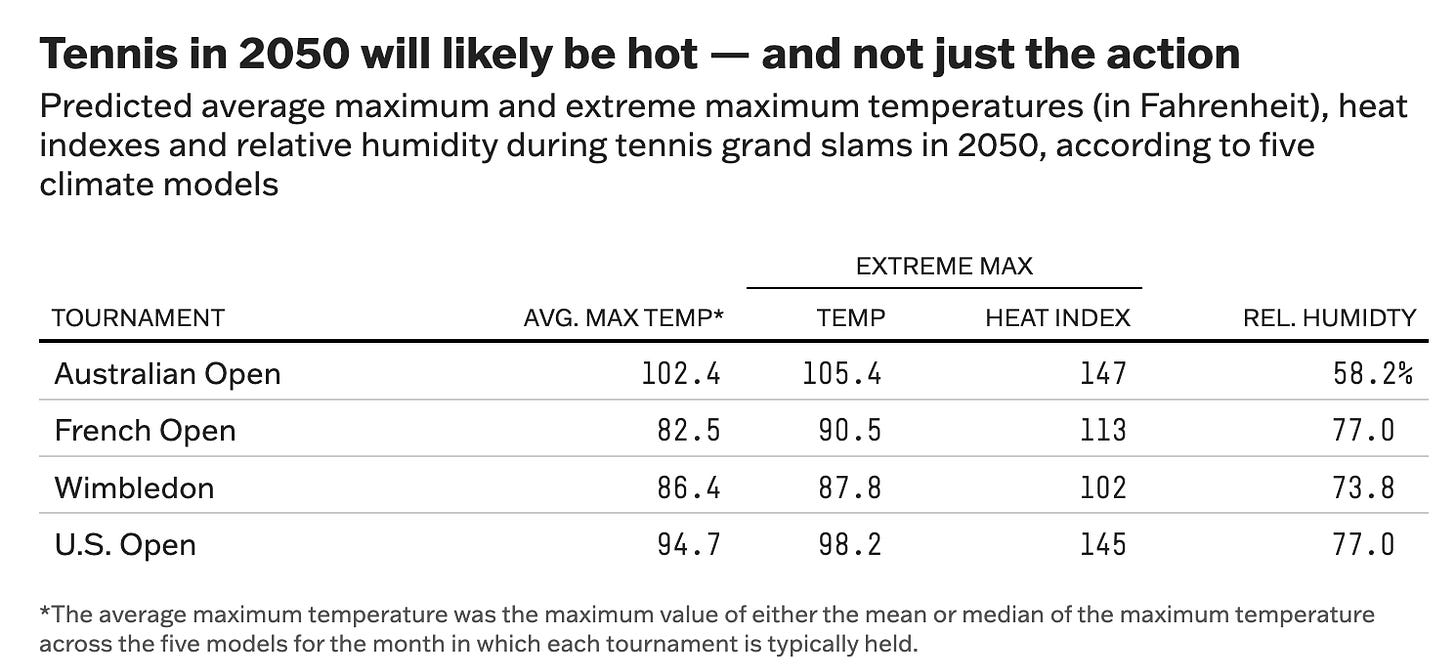

I’ve discussed previously the impact increased heat will have on match play, where events like the Tokyo Olympics put on display the unique vulnerabilities individual sports face in extreme heat conditions. However, while the phrase “global warming” might conjure images of cheerful sun and piña coladas, the actual impact increased global temperatures has on local weather patterns results in an increase of all types of severe weather events. So it’s not just heat waves that the sport needs to worry about adapting to, but also increased rainfall like we’re seeing at this year’s Roland Garros.

For example, on the other side of the channel, rainy periods in the UK and Ireland are estimated by climate scientists to be almost 20% worse due to changes in the climate caused by human behaviour. By literally increasing the amount of heat energy present in the climate system, global warming “supercharges” already potent weather patterns, giving rise to worse and stronger weather patterns than before. The result isn’t just longer periods of cheerful blue skies, but wetter and rainier summers across Europe.

Arguably, the rain we’re experiencing at this year’s Roland Garros is not a one-off thing. Due to climate change, we can anticipate a “wetter, damper and mouldier future,” one which will impact not only our ability to efficiently schedule tennis tournaments, but also crucial industries such as agriculture. Adaptation to heat is only one way in which the tour must consider the impacts of climate change; increased rainfall is another concern to mitigate, whether through more strategic tournament scheduling or increased use of roofs (neither of which are exactly cheap or easy options).

There is almost a poetic futility to it, the way that humans might try our hardest to construct games with intricate rituals only to be usurped by mother nature once again. The rain at Roland Garros and the climate change which fuels such errant weather patterns reveals a deeper question at the core of modern sporting culture. Is flying around the world for the tour truly sustainable in a world with increasing climate pressures? How can we mitigate the impact tennis has on the climate so that we might be able to play matches without the disruptions and harms we experience now?

As climate change becomes a growing challenge across the world, tennis is just one of many areas in which adaptation will become more of a necessity than ever before. First is the obvious question of mitigation: how will tennis ensure that tournaments can still run, even with the uptick in freak weather events that are quickly becoming the new normal? Second is a longer, more difficult reckoning with the way in which the sport itself has exacerbated climate change through increased consumption and the sheer amount of travel the tour demands. This is much less easy to do, but arguably the more important task at hand.

There are easy areas to look at first: the sponsorships from corporate entities like Barclays who actively provide billions of dollars to the oil industry, the use of private jets, the unsustainable procurement contracts which exacerbate tournament waste. None of these are easy divestments and the pessimist in me believes they might never happen at all. Yet, interrogating the relationship between tennis and climate change is crucial if the sport wants to adapt to the demands the modern world places upon it.

While the rain at Roland Garros is a mere annoyance for now, this is not an isolated weather incident. Between the issues with heat we will inevitably experience during the North American hardcourt swing this year and the rainfall we are faced with now, climate change remains a relevant threat to the functioning of the sport itself. In life, much like tennis, when it rains, it pours, and Roland Garros is proving no different.

Great article! I attend the Citi Open (DC) and it can be brutally hot, with rain mixed in. It’s hard on players and spectators. No covered courts beyond the Slams, so we’ve seen it be a problem for the whole tour. Some good things to think about, and will be interesting to see where the sport goes with it.

It's so rarely mentioned that the expensive seats are so often empty, despite tens of thousands of actual fans being a few meters away. Those seats are becoming prohibitively expensive, and yet no one is sitting in them.