This week’s Laver Cup has felt quite odd as a tennis fan. I have spent the past year watching those in my general circle in the tennis space go from condemning this tournament as morally wrong, to seeing endless content uncritically tweeted about it. The sudden about-face on what Laver Cup represents within our community was jarring, and I wasn’t sure what to make of it. It felt like I was the only person who’d not gotten the memo, that I was the ghost at the banquet, dredging up reasons to hate on something that so obviously brings others joy.

I’d spent all of last year watching people get blocked by Laver Cup for mentioning the abuse case, only for them to be begged to be unblocked so they could look at content this year. What I had thought was a general community norm–that this tournament is uniquely bad due to reasons mentioned before–was about as solid as a sand castle at high tide. And this is what was jarring, not necessarily just people being excited about something.

It made me re-evaluate the way we view activism within our community. This is what I want to get to the heart of with this piece–how can we move toward a more effective way of talking about issues like abuse within our community? The current discourse feels garbled, and while part of this is attributable to the way twitter works, I think it’s additionally complicated by the way in which our community is structured in the first place.

I therefore want to examine the role that morality plays within fandom (in particular the tennis fandom). Why do we adopt moral positions? How do we approach our own moral contradictions? What does this say about our ability to imagine new futures? In examining these questions, I hope to move the dialogue forward regarding what “activism” might even embody within the online tennis space.

What the hell is Laver Cup anyway?

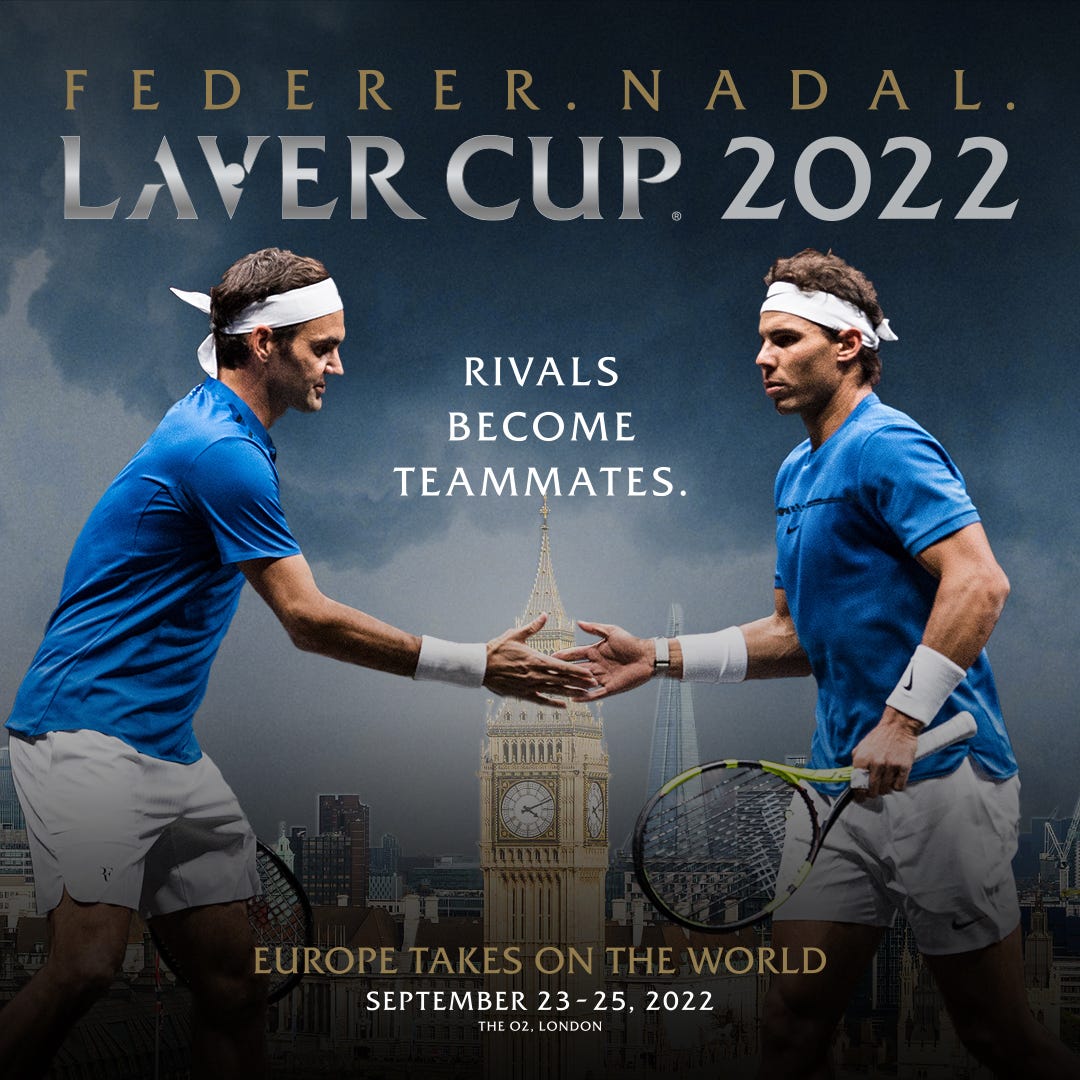

I realise not everyone is as chronically online as I am, so I think what Laver Cup is and why it’s been deemed “problematic” is important to clarify here. The Laver Cup is a men’s tennis exhibition created by Roger Federer’s management company in conjunction with Brazilian businessman Jorge Paulo Lemann and Tennis Australia in order to bring tennis to places which don’t usually have ATP tour events. The format is based on golf’s Ryder Cup, in which a team composed of players from Europe compete against players from the rest of the world. The more casual exhibition vibe is therefore intended to draw in fans who might be turned off by the stuffier image that tennis tends to have.

So far so good. If you’ve read my writing before, you know that I should think this is a good thing–anything that appeals to new audiences ought to help grow the sport. It seems contradictory for me to be complaining about lots and lots of new user generated content when this is something I usually very vehemently advocated for. However, Laver Cup is still tainted by critiques that I have for the rest of the tour–in particular, the way that it has approached abuse of women and girls within the tennis space.

Laver Cup is a particularly problematic tournament when it comes to issues of abuse. First, it was on Laver Cup tournament property that part of the Zverev abuse case occurred. A tournament official is directly reported as having witnessed some of the aftermath, and yet this abuse was promptly papered over in favour of maintaining the image of the tournament. Zverev continued to be selected to compete for Team Europe, and the tournament vigilantly blocked anyone who mentioned the abuse case in their social media comments. The responsibility therefore is not just limited to Zverev himself or the tour in abstract: this specific tournament itself is culpable for enabling this abuse.

This papering over of abuse was exacerbated by this year’s Laver Cup. First, the focus of the tournament became Roger’s retirement and to a lesser extent the Big Four rather than any of the PR issues which had surrounded past iterations of the tournament. Now it is of course totally logical to care about the retirement of one of the most beloved players the sport has ever seen–I’m not working on an extensive article about Federer for nothing. However, this has successfully shifted the dialogue away from the way in which tennis (and Laver Cup in particular) has directly perpetuated the abuse of women and girls on its own tournament property.

I think it would be wilful blindness to not interpret at least some of what happened as an effort to rehabilitate the image of this tournament after what has occurred. In particular, I am thinking about the way Zverev was invited to the tournament with zero actual connection to the matches being played–or the way those connected to the tournament have referred to the abuse as a “private matter.” I feel like the ghost of Banquo, seeing the negatives in a tournament I have really only seen positive tweets about. It feels like whiplash, going from “I was blocked by Laver Cup” to “this is Roger’s last ride, give it a rest.”

Now, I sound very salty and curmudgeonly here so I feel I need to add some nuance into my positions. I don’t think people who enjoyed or participated in Laver Cup are bad people, or that you always have to be consuming ethical media to be a good person. This article is a self-callout–I want to examine why I felt the way I did because I feel it has something to say about the wider way in which we discuss tennis. I therefore wish to interrogate my own impulses which are not conducive to constructive dialogue in order to try and move toward a model that is more beneficial for the tennis community as a whole.

What is the point of online activism in the first place?

So why did people even care about Laver Cup in the first place? Why pour countless hours into cancelling others for minor indiscretions only to wholeheartedly engage with the very material used to justify “call outs”? I think at this juncture it’s important to examine why we choose to concern ourselves with matters of morality online. I want to disentangle genuine moral concern from the general outrage we all experience online, in order to better examine how we can build a more constructive dialogue about abuse within sport.

Beneath the word morality, James Baldwin explains, “we are confronted with the way we treat each other.” At the heart of morality, therefore, is the question of how we interact with each other, with a special attentiveness to our own subjective realities as human beings. I do genuinely believe that most people engaging in a moral dialogue within the tennis sphere are doing so because they want to help others. However, I feel that something often gets lost in translation along the way, and the dialogue frequently devolves (as it is wont to do online).

So, if we all want to do what’s right, where is the issue? The problem is that the limitations of our virtual space have condensed our idea of what “activism” might even constitute. Like a game of “telephone,” the idea that our consumptive habits might have moral implications has collapsed into the idea that your worth as a person is determined based on what you consume. The question suddenly shifts from “how can I act ethically” to “how can I consume most ethically.” Sometimes I feel myself sliding into the easy temptation of feeling like an ethical person because I am a fan of “ethical” players. However, just supporting the “right” person makes me no more of a moral person than choosing one brand of butter over another.

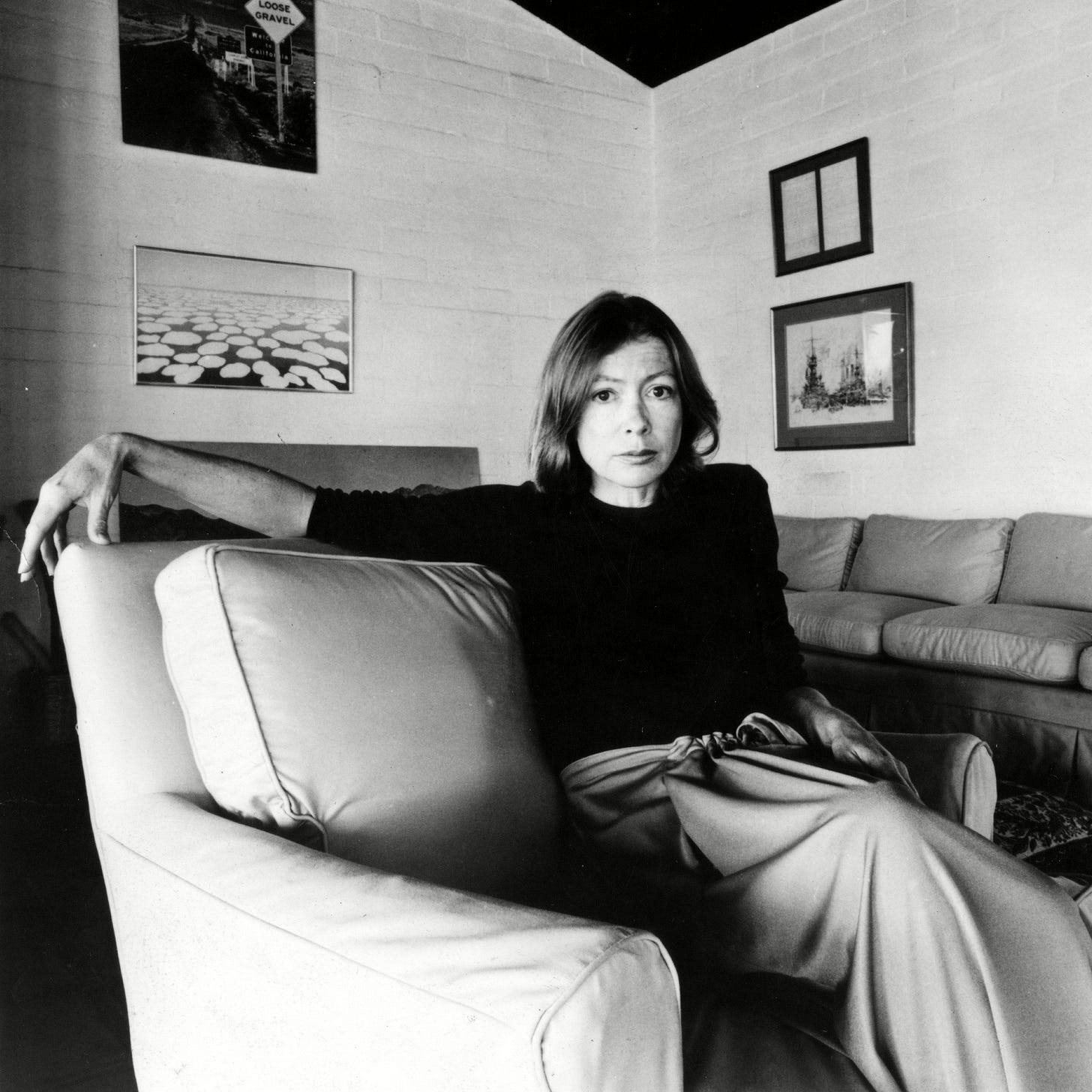

In her essay “On Morality,” Joan Didion particularly clarifies the difference between this kind of self-righteousness and genuine moral action.

“Of course we would all like to “believe” in something, like to assuage our private guilts in public causes, like to lose our tiresome selves; like, perhaps, to transform the white flag of defeat at home into the brave white banner of battle away from home. And of course it is all right to do that; that is how, immemorially, things have gotten done.”

I find Didion’s piece so prescient, because I frequently find myself slipping into the same tendencies. I feel guilty about things I have gotten wrong in the past, so I focus on seemingly as morally correct as possible in the present. I want to be a good person, so by sheer force of will I try to convey myself online as someone who cares about ethics. But at the end of the day, these rather selfish desires prevent me from being open to the very dialogue necessary to build a genuinely transformative space within tennis.

Didion continues with her critique:

“But I think it is all right only so long as we do not delude ourselves about what we are doing, and why. It is all right only so long as we remember that all the ad hoc committees, all the picket lines, all the brave signatures in The New York Times, all the tools of agitprop straight across the spectrum, do not confer upon anyone any ipso facto virtue.”

I think this is the heart of the matter. Frequently I find myself undertaking an activist cause online because I personally want to have virtue: I want to see myself and be seen by others as a virtuous person. However, the genuine transformative work required to confront issues like abuse within tennis needs to be undertaken regardless of how it impacts my own personal self-image. I have deluded myself that all of my snappy little tweets amount to something when in reality they do no more to make me an ethical person than any other choice.

The efficacy of our activism as a community often feels stagnated to me because it is framed around consumption rather than genuine change. I don’t think people who enjoy Laver Cup condone abuse–this would be an incredible reach when the truth is far more nuanced. However, our ability to generate change becomes limited when we focus our “morality” on criticising the consumptive habits of others. We will always be hypocritical, but to be blind to our own contradictions is the greatest self deception of all. Self-righteousness will always be a cheap substitute for genuine moral action, and I think this is what this iteration of Laver Cup has taught me more than anything else.

Now, it ostensibly seems as though I am exactly what I seek to critique. Here I am, dredging up all the reasons why Laver Cup is a particularly problematic tournament and explaining why I feel uneasy seeing so much uncritical coverage of the event all over the timeline. I think my issue with the extent of the excitement over Laver Cup has more to do with the way it has exposed the flimsy foundation on which “twitter activism” (if such a thing is even possible) is built on. What good does it do to have a link to Olya’s story in your bio when you then proceed to uncritically retweet and post hours of content of the very tournament which perpetuated her abuse?

It does feel odd to see people who were in the past hypervigilant about, for example, listening to problematic bands, suddenly invested in this tournament and promoting its content widely. It’s weird to see people ostensibly very concerned with morality suddenly tweeting “maybe this tournament does have rights.” I don’t know how to feel about it, because I am also an imperfect human being. I know that Paul McCartney has done horrible stuff, and yet I still listen to his music. Does this diminish my ability to make my own statements about moral behaviour? I’m not sure.

How to engage with problematic media feels like a question as old as media itself, but the advent of the internet and proliferation of various social media platforms has made this particular question into a complicated dialogue. The reason I write this is not because I’m sitting atop some mountain of books with some sage advice regarding the perfect solution to this question. I’m a person just like everyone else, so in a sense this article is just as much me trying to work out my own thoughts as it is an editorial about a tennis exhibition.

Being a fan of tennis has inherent moral complications. Being a human being in and of itself is an existence which is periled with tricky moral questions which lack an easy resolution. It’s nice to pretend that this is not the case, that these conflicts can be tied up in a neat little bow of what is “ok” and shoved neatly under the bed, but to do so would be the ultimate self deception. All of the self-righteousness in the world will never amount to a genuine concern for morality, so at the very least it is crucial to not let the easy temptation of righteous indignation distract us from the actual matter at hand.

I think, however, that our own hypocrisy and imperfections can be a site for change in and of themselves. In recognising that we are not in fact perfectly moral beings, we are able to open ourselves up to greater opportunities for genuine transformative change. However, this is genuine work and effort, and as a chronically lazy person I also acknowledge how difficult that can be. Ultimately, though, I hope that our own fallibility can serve as a gateway to an activism that operates from a place of joy and solidarity rather than constant policing.

The particularities of digital activism

My critique is ultimately quite simple: somewhere along the way we collectively mistook morality for self righteousness, which has transformed our activism from a transformative dialogue borne of solidarity, into a hollow moral code consisting of carefully constructed symbols that are capable of being discarded at a moment’s notice. However, I think the particulars of how this tendency plays out are important. I therefore want to focus on a few things I find myself doing, when I could be using my energy toward more constructive ends.

First, it is exceedingly easy for me to conflate the structural and the personal. It’s important to critique structural issues–after all, questions about racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism are all at the heart of what is wrong and outdated about tennis at the present. However, the emphasis on “calling out” individuals means that the narrative of what we are critiquing often gets lost. Individual shortcomings become opportunities to descend on a user who has been found out to be doing the bad thing.

I find it quite interesting to see the way people on twitter discuss structural injustices. I occasionally see people tweeting about how they want a player to slip up and do something problematic—I assume so that they are finally “exposed” as the horrible person they are. However, I have to ask myself why do we want people to be acting immorally? Why would we want that bad act to exist in the world? We find ourselves wanting to catch others in the act of moral transgressions so we can pin systemic harms onto the individual–this then excuses how we treat these individuals because, after all, we’re acting morally, aren’t we?

I therefore think it is imperative to remember to resist the temptation of self-righteousness. Who are we helping with particular actions online? In some instances it is absolutely necessary to call out people who have acted in a problematic way–see the Berrettini gorilla emoji controversy. However, what does crowding the mentions of an individual twitter user about their take on the matter do? In an ideal world, calling someone out should be for the purpose of education rather than sheer punishment. No amount of shame or sadness an individual feels is going to change an act they’ve already done–crowding the mentions of a random twitter user is not going to materially change anything for marginalised groups. However, our shortcomings are opportunities for growth and should be treated as such. By focusing on building a better future, it’s easier to keep the dialogue constructive.

Second, I think I have a tendency of essentialising the discussion of morality into a clear cut dichotomy of good and bad. Either you’re unproblematic and can be engaged with, or you’re problematic and therefore must be shunned. I do think accountability for our mistakes is critically important. However, this black and white thinking shuts down conversations before they have even begun.

This essentialising tactic is apparent once you notice it. Say someone tweets/says/does something that is construed as sexist/racist/homophobic etc. This person then becomes sexist/racist/homophobic etc–their entire identity is thus defined by this error. By essentialising others into these unpleasant categories, harassment becomes justified and even normalised. Essentialisation is another process that occurs naturally due to the limited nature of the internet. We are presented with words rather than the whole of a human being. However, who are we really helping by doing this? Is it materially going to change how the tour approaches abuse to come after some teenager running a stan account for a player who is friends with an abuser? I instead think this might actually turn more people off from the movement than it gains. I reiterate that accountability for problematic action is crucial, but it must be done in a nuanced way.

Third is the emphasis on outrage. Of the three vices I outline here it is this one that I far and away find myself indulging in the most (although I know myself to be guilty of all three. This is all a self callout!). Twitter makes outrage incredibly easy. It feels so good to ratio someone or to reply with the perfect zinger. Instead of taking the time to think things through, it is so easy to just tweet something snappy and close your phone. One of my favourite parts of twitter is the feeling of a spirited debate, but this is something I admittedly need to stop engaging in as it’s counterproductive to most of the positions I hold offline. Infighting about inane quibbles limits our ability to critique the actual structural problems in tennis–the classism, racism, sexism, and homophobia we know are present in the sport.

It’s important to remember why discourse is important in the first place–it allows us to debate and construct new futures. However, this sort of constructive and transformative dialogue can only happen when both parties are actually working to put forward new ideas in good faith–and good faith is about the last thing my Paul McCartney reaction images are. I therefore think it’s important for me to remember why I engage in discourse in the first place–to figure out a better way of doing things.

Now, you might ask, why should we care about your personal flaws when existing on twitter? What impact does it actually have on the tennis space? My answer to this is quite pragmatic, and quite a few people probably disagree with it. Ultimately, if you want your social movement to be able to make some sort of change, it behoves you to make it appealing to others to join. Activism from a place of fear–fear that you will be the next one who is exposed or condemned–is not an appealing movement to join. Instead, creating a space which is actually enjoyable to exist in is crucial in tandem to other efforts within the tennis space.

For me in particular, this means cooling it on the performative statements surrounding Laver Cup. Calling people out will only go so far. Indeed, the people in this community should be seen as my compatriots rather than foes to needlessly call out. The importance is on figuring out an activism which actually accomplishes something rather than simply serving the purpose of selfishly making me feel good.

What does this mean for the future of tennis?

There are endless essays and thinkpieces on here about what the “future of tennis” looks like. However, these futures are almost always tied to the material concerns of the present. By this I mean that they often inadvertently reproduce current oppressions happening in the present. Journalists who ask how it’s possible for anyone to see the Laver Cup as anything but good are imagining a different future of tennis from the new future I think that we need to imagine–one in which marginalised identities are not only comfortable, but also able to use the site of the sport itself to push for further change in the “non tennis” world.

I think part of transformative action means leaving the twitterverse, no matter how fun it may be. Investing in side projects like substacks and artistic ventures allows our dialogue to transcend the simplicity of the social media space. I’m not entirely sure what transformative action within the tennis space might look like, but that’s not up to me. The point of a community project is that we work together to make our space more inclusive of those traditionally marginalised from the sport, however that may manifest itself.

True transformative action comes when we work in good faith to imagine a new future of tennis. Things like Laver Cup discourse are symbolic of a wider breakdown in communication when it comes to working toward this project. Somewhere along the way, moral complications become points to be scored and hot takes to be tweeted. Perhaps I’m being too optimistic here, but I believe we owe it to ourselves and those in our community to build a sport which is less oppressive than before. It is crucial to look at the matter with as clear of eyes as we can muster, lest we slide into the delicious temptation that is righteous indignation. The way forward is not partisan infighting but rather a shared sense of ownership and solidarity.

A great and much-needed article, May! The way that online/twitter “activism” has made people’s mindsets shift from “how can I act most ethically?” to “how can i consume most ethically?” is something that needs to be examined and critiqued more. Love reading your work, as always :)

Excellent essay, May! A very thoughtful and personal take on the Laver Cup (and tennis tournaments in general!)